CAFFE TAZZA

The Quality of the Conversation

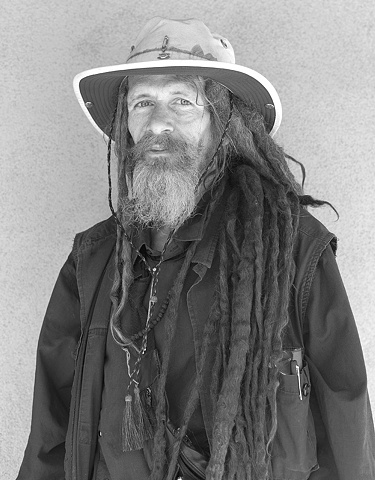

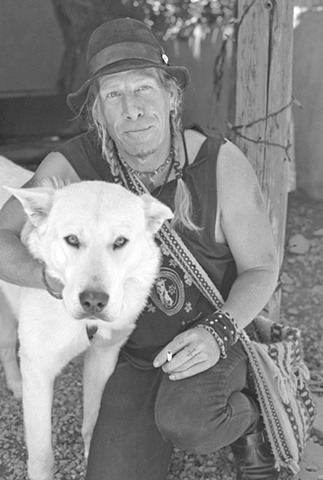

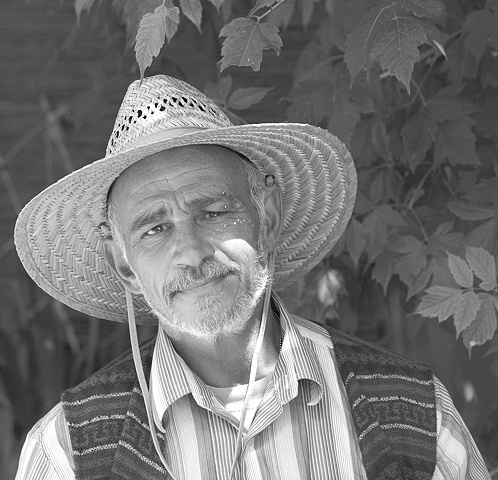

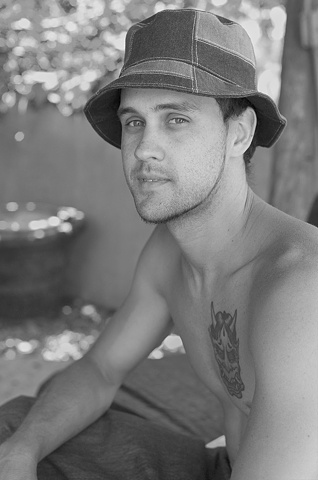

Of all the coffee shops in Taos, New Mexico, why Caffe Tazza? Sambhu, a local musician and artist who has been coming to the café since its founding twenty-six years ago, says it‘s “the quality of the conversation.” It’s true that the impromptu discussions are wide-ranging, intelligent, sometimes contentious, occasionally incomprehensible – but always fascinating. When I moved to Taos in 2001, I took a part-time job at Tazza while waiting for my teaching job to begin. As I stood behind the counter, preparing coffee and listening in, I thought, “I am definitely not in Bettendorf, Iowa, any more!” The regular participants then included not only Sambhu, but Caress the poet from London who dressed in sorcerer’s garb, Jesus a sweet bear of a man who played saxophone and flute, Willow the Tarot Card reader who had previously been known as Leaf, and local artist Anita Rodriguez, who sparked some of the most challenging dialogue. And the roots of the building itself go back far – it was built in the 1830’s, and the rear part was once Kit Carson’s horse stable.

Over nine years later, having made a home in Taos and having worked here as professor and gallerist and artist, I found myself drawn once again to Caffe Tazza - this time to hang around on the patio talking to people, listening to music, and making photographic portraits. Why Tazza? Not only because it was just plain fun and the lattes were good, but because I needed an antidote to the increasing homogeneity of American and world culture.

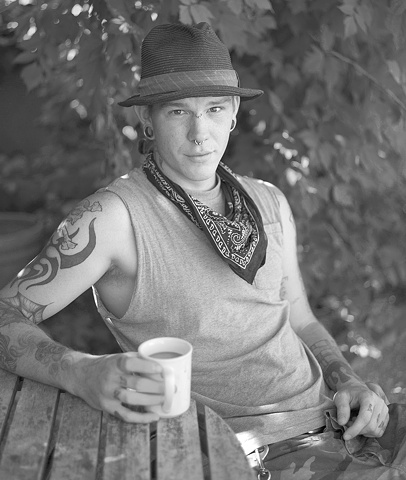

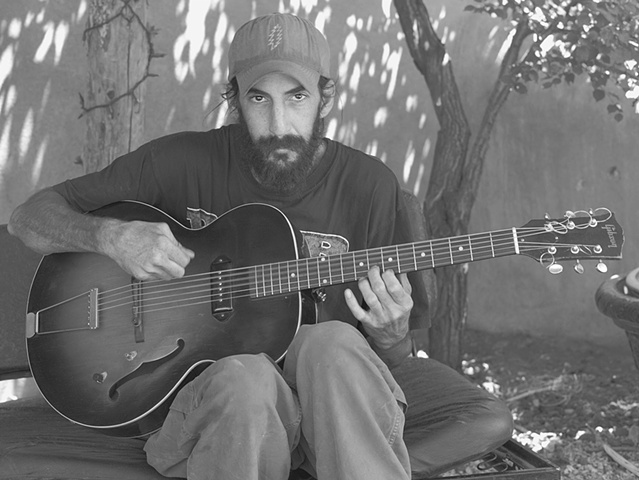

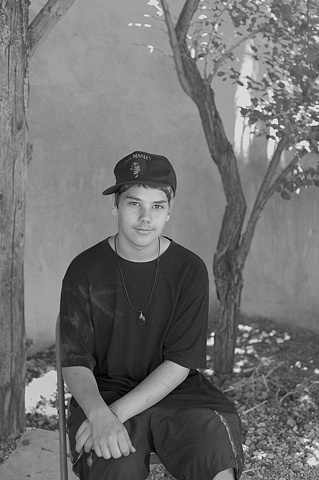

We’re lucky in Taos – we have an often controversial but never dull mix of cultures. But Caffe Tazza in particular attracts individualistic free spirits, both locals and pilgrims traveling through. In the past few months, I’ve met many young people who are on the road – they’ve said that locals told them Tazza was a welcoming place. They loiter on the patio, exchanging stories, playing chess, strumming guitars and singing. They share knowledge of where they might find a free meal or a place to sleep. Then they continue on their seeking journeys.

At Tazza, the locals connect with their community in Taos. Sambhu says that he uses his hour or two in the café every morning as his “office hours – people know where to find me, and don’t come to my house and bug me.” He wants to talk to people face-to-face, not over WiFi, and considers his routine there his center of gravity. Customers from the West Mesa and Tres Piedras share permaculture and earthship building tips. Nearby apartment-dwellers and gallery owners stop in for coffee. Tourists drop by, intrigued and sometimes bemused.

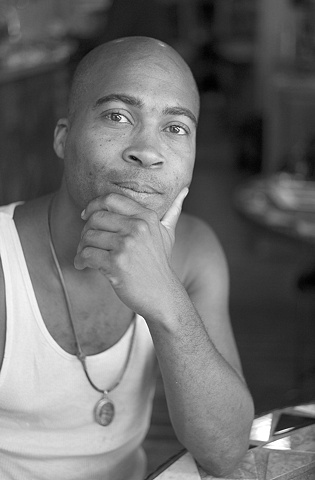

As a part of the reinvention that they have embraced, many of my portrait subjects have given themselves new names. Sambhu’s name was given to him by a yogi in England, whom he calls a self-realized person. Sam and bhu mean absolute and relative, representing at once both sides. And there are Pythagoras, Sparrow, Tall Blond Guy, Sunkmanito Ho Waste Hokshila, Whitebeard, Agent H. Solo, and Hero. Even some of the birth first names are superb, such as Freedom, Jomo (named after the father of the Kenyan nation), Israel, Xander, Kasper, and Lilith. The dogs on the patio carry such monikers as Fellini, Casey Jones, Kiva, Cloud, etc.

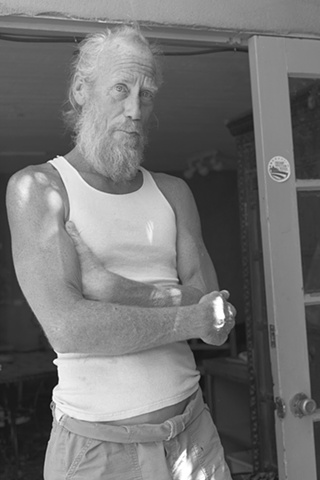

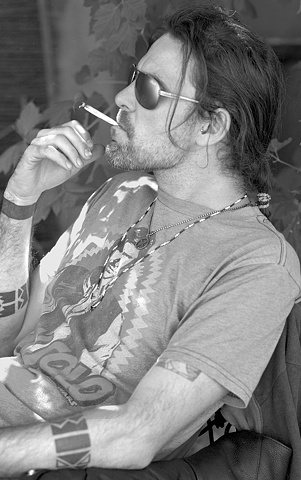

The stories are as rich as the names. Cindy, a belly dancer and one of the few women regularly inhabiting Caffe Tazza, proudly tells of giving birth to three children. The first two births were attended by friends - but for the last birth she was alone in a hundred-year-old cabin in Taos Canyon, and “caught him herself.” Tall Blond Guy relates the satisfaction of building his own home on the West Mesa for a few thousand dollars, though he expresses concern about safety issues in his community. But, he says, “If we wanted generic, we’d live generic. Flavor, like spice in food, is what people want.” He hitched a ride to Taos with a former director of the Hanuman temple, after his years of following the Grateful Dead band ended with the death of Jerry Garcia. He had first learned of Taos from the film Easy Rider, and wanted to “check out all the hippies living out there.” He says the ghost of Dennis Hopper is still here in Taos.

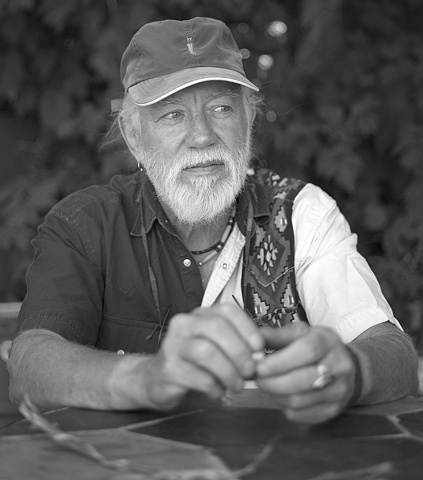

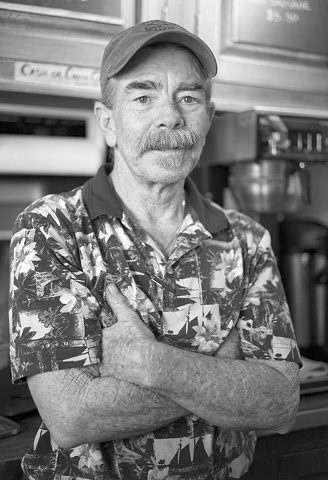

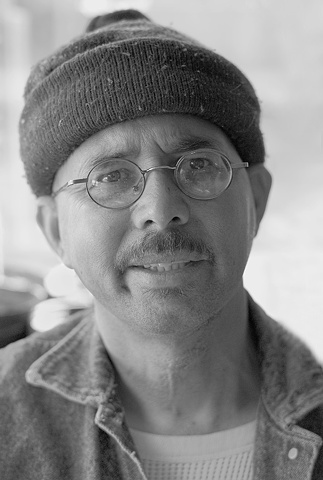

One of the long-timers is Frank, who came to Taos in 1971, thirty-nine years ago. He too mentions the Grateful Dead, quoting from the song, Truckin’: “What a long strange trip it’s been.” He lived in Llano Quemado when he first arrived, and thought he had arrived from California into Old Mexico. There were few paved roads, and only the privileged had electricity and television. He lived by the hot springs, bathed in them every morning, fed the bears at night. Since he had come with carpenter tools and skills, he soon entered “the hierarchy of those who had at least $10 in their pockets.” House rent was $25 a month, so he learned that he didn’t have to work as hard as he had thought, and kicked back. After working security in local bars and buying and selling small parcels of land over the years, he retired to Tres Piedras. He hitches rides into town (he used to ride a horse, but says he was banned because he didn’t clean up after his horse in the plaza). He considers Caffe Tazza his family hub. He says it’s like Cheers, Taos style!

Frank, now sixty-one years old, thinks back to the days when the Mountain Rats, a motorcycle gang existed – not violent, he says, just your neighbor. He recalls the native Americans wrapped in their blankets who used to gather on the plaza. He reminisces delightedly about crazy people who used to walk freely around town: “We used to like that. Old ladies talking to spirits in the sky. An ex-sheriff, 90 years old, still with his badge on, cowboy hat like McCloud, gun in his belt – but they took the bullets away.” Frank fears that Taos is changing so much that it may be a mini-Santa Fe by the year 2020. But perhaps not: “Taos is a sovereign nation. We don’t really abide by everybody else’s rules.”

A newer arrival is Sparrow. She arrived six years ago, attracted by affordable land, an interest in permaculture, and open rules for home-schooling her children. Like many inhabitants of Taos, she works several jobs. Sparrow stuccoes homes, raises goats and ducks (no chickens, “they are an alien half-breed or something”), works at the café, and lovingly tends her growing family.

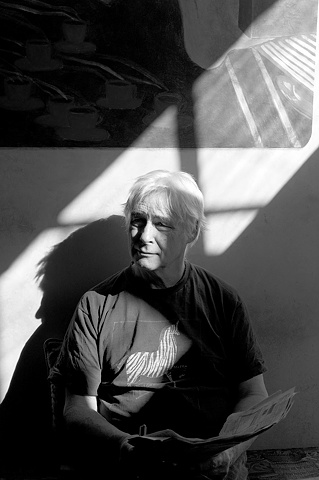

John the Poet started writing seriously when he moved to Taos. He had worked in construction until he was injured on the job, and was visiting Taos when a tree fell on his home in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina. There was nothing to go back to, so he stayed. He spends much of his day inside the café, writing poems in longhand, penning political pieces for The Horsefly alternative newspaper, and learning to use his computer. He chose Tazza for his literary hangout because he likes the architecture, the open mike event on Friday evenings, and the “eccentric characters.” Diversity is always what he’s been looking for.

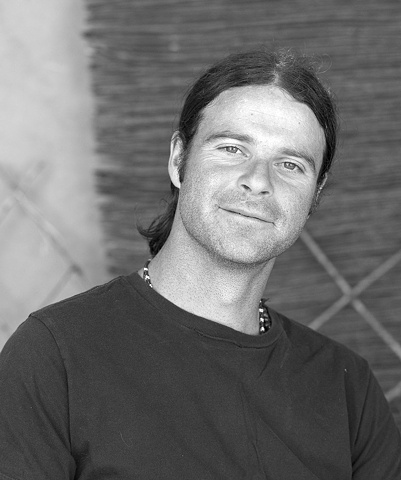

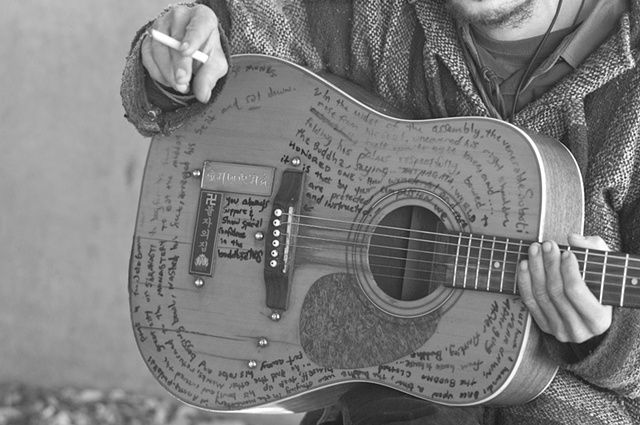

Strumming his guitar with Buddha‘s sayings handwritten all over it, Timothy sits on the outdoors patio. He creates art: music, oil paintings, jewelry, twenty-five styles of walking sticks, and dreamcatchers. He never sells his creations, but prefers to barter – last winter he traded some jewelry for a small wood-burning stone.

Many of the regulars at Caffe Tazza don’t lead easy lives. But most of them wouldn’t have it any other way. Sambhu, who has worked hard but artfully as a waiter for many years, believes that “without struggle, you’re not really alive.” And Tall Blond Guy says, “That’s what your life is for, isn’t it? To really live it, the good and the bad. If you go to a nursing home and ask the people there, they’ll say, Live your life.”

Caress, the poet I met during my first months in Taos, wrote: "Creation is that delicious eloquence that lies within paradox." That seems to reflect life at Caffe Tazza: creative, disordered, delicious, tolerant, obstreperous, nurturing, durable, paradoxical, unique.

Robbie Steinbach 2010

Addendum: Caffe Tazza closed its doors in 2017. An immense loss.